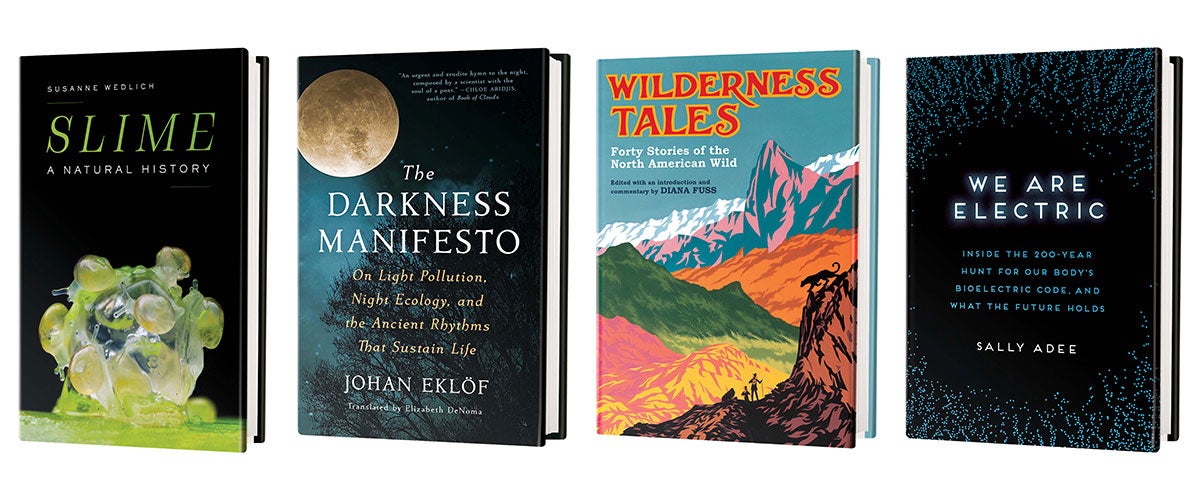

Slime: A Natural History

by Susanne Wedlich

Translated by Ayça Türkoğlu

Melville House, 2023 ($27.99)

In Slime: A Natural History, science journalist Susanne Wedlich preempts her readers’ repulsion. Although “we are all creatures of slime,” she writes on page 2, the mere mention of the name connotes images of sickness, death, and other taboo experiences of modern, “hyperhygienic” life that we often try to keep unspoken and out of view. Wedlich intends to change the perception of slime from something that disgusts to something that fascinates.

In this way, the book quickly takes on a persuasive tone, with Wedlich dismantling negative preconceptions. A literary and sociological analysis of slime visits references from movies such as Alien and Ghostbusters and Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Lolita, where it’s a metaphor for “everything that can be dangerous, disgusting and simply wrong about sex,” to the campaign for sanitary reform in the 19th century and our aversion to powerful odors as an indication of uncleanliness.

This compelling cultural overview beckons readers toward the more science-heavy parts, where things get a bit stickier. Defining what slime is “may be as slippery as the substances themselves.” Although mud and muck were thought of as a source of life by the ancient Egyptians, it wasn’t until Darwinist Ernst Haeckel hypothesized that primordial slime on the ocean floor contributed to the origins of life that the study of slime gained some attention.

To this day, many biological slimes haven’t been researched enough to know the details of their structure and behavior. The general qualification that they exist between fluids and solids allows Wedlich to take a wide view: “If it looks like slime, behaves like slime, is regarded as slime or simply catches my attention in a slime-like way, it belongs in this book.”

This smart decision shapes the stories that follow. We hear about snails that surf their own mucus for forward propulsion, digestive secretions that help defend our bodies through a mucosal immunity, and bioadhesives that create “marine snow,” a continuous shower of organic rain that delivers energy to the deep ocean. Wedlich’s knack for unfolding these natural histories makes her book ooze with charm. —Michael Welch

The Darkness Manifesto: On Light Pollution, Night Ecology, and the Ancient Rhythms That Sustain Life

by Johan Eklöf. Translated by Elizabeth DeNoma

Scribner, 2023 ($26)

As a Swedish conservationist, Johan Eklöf urges us to think of light pollution as more than a nuisance that obscures our starry skies. In a series of well-researched vignettes, his message is a plea for nonhuman species: artificial lights disrupt migration patterns, mating rituals, pollination practices, insect biomass, and much more. Eklöf highlights the startling sprawl of these lesser known consequences without evoking a hopeless or cynical tone. Instead the book is a reflective reminder that our control of the world is as delicate as the smallest of species affected by it. —Sam Miller

Wilderness Tales: Forty Stories of the North American Wild

edited by Diana Fuss

Knopf, 2023 ($35)

Featuring writers such as James Fenimore Cooper, Karen Russell and Anthony Doerr, this anthology charts a modern course through a long-established genre. The unconventional selection of wilderness stories takes us from swamp to tundra and from Plymouth Rock to today’s crisis point in the Anthropocene as it maps the complex evolution of our society’s relationship with wild places and the shifting tales we tell about them. Although editor Diana Fuss organizes the book around themes as divergent as “Fire and Ice” and “Women and Panthers,” every story asks us to reexamine “what wilderness may mean and why it compels us.” —Dana Dunham

We Are Electric: Inside the 200-Year Hunt for Our Body’s Bioelectric Code, and What the Future Holds

by Sally Adee

Hachette Books, 2023 ($30)

A decade ago, when a researcher sent an electric current through journalist Sally Adee’s brain, she momentarily became a sharpshooter in a simulated military operation. The experience left Adee with a lot of questions. In her debut book, she paints a riveting (and often humorous) picture of 200 years of research on the bioelectricity coursing through our bodies, from debates over twitching frogs’ legs to devices developed to give sensation back to people with traumatic nerve injuries. In this bioelectric age, Adee argues, “we are electrical machines whose full dimensions” are ripe for discovery. —Fionna M. D. Samuels