Global warming is making the atmosphere more hostile to the formation of tropical cyclones. By the early 2010s there were about 13 percent fewer storms across all oceans than there were in the late 19th century, according to a new study published on Monday in Nature Climate Change.

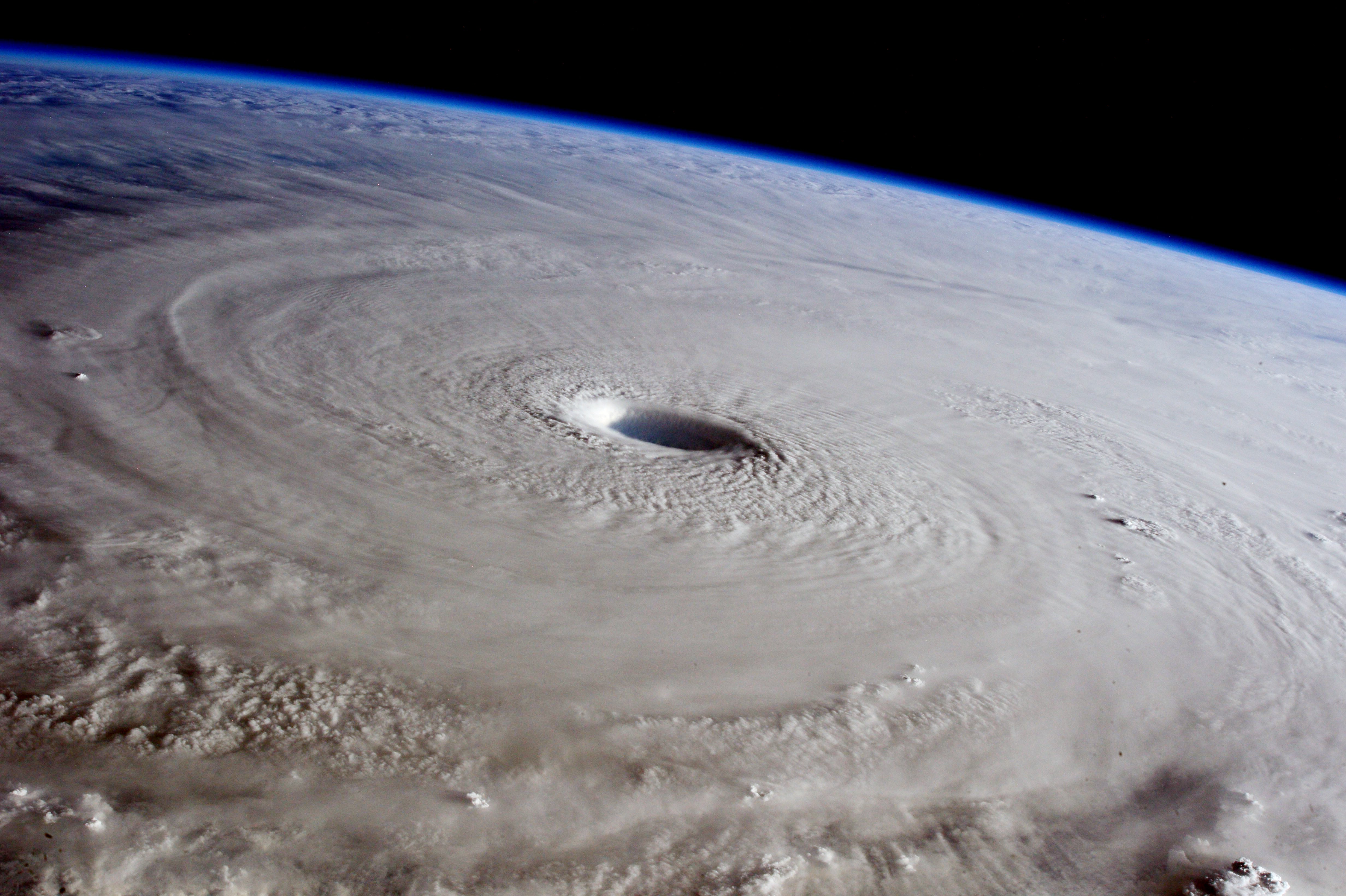

But having fewer hurricanes and typhoons does not make them less of a threat. Those that do manage to form are more likely to reach higher intensities as the world continues to heat up with the burning of fossil fuels.

Scientists have been trying for decades to answer the question of how climate change will affect tropical cyclones, given the large-scale death and destruction these storms can cause. Climate models have suggested the number of storms should decline as global temperatures rise, but that had not been confirmed in the historical record. Detailed tropical cyclone data from satellites only go back until about the 1970s, which is not long enough to pick out trends driven by global warming.

The new study worked around those limitations by using what is called a reanalysis: the highest-quality available observations are fed into a weather computer model. “That’s something which gets us close to what the observation would have looked like,” essentially “filling in the gaps,” says study co-author Savin Chand, an atmospheric scientist at Federation University Australia. This gives researchers a reasonably realistic picture of the atmosphere over time, in this case going back to 1850. Chand and his team developed an algorithm that could pick out tropical cyclones in that reanalysis data set, enabling them to look for trends over a 162-year period.

They found the 13 percent global decrease in tropical cyclones over the period of 1900 to 2012, compared with 1850 to 1900 (the latter is widely considered a pre-global-warming reference period). There was an even larger decline of about 23 percent since around 1950, around the time global temperatures started to noticeably rise. The declines vary in different parts of the ocean. For example, the western North Pacific saw 9 percent fewer storms, and the eastern North Pacific saw 18 percent fewer over the 20th and early 21st centuries. And the North Atlantic results indicated a peculiar trend, showing an overall decrease over the past century—but with an uptick in recent decades. That shorter-term increase could be linked to natural climate variations, better detection of storms or a decrease in aerosol pollution (because aerosols have a cooling effect, and tropical cyclones thrive on warm waters).

The study provides crucial ground-truth information for evaluating climate model projections of further future changes in cyclone frequency, says Kimberly Wood, a tropical meteorologist at Mississippi State University, who was not involved with the paper.

Chand and his colleagues link the decrease in tropical storm frequency to changes in atmospheric conditions that constrict convection—the process where warm, moist air surges upward in the atmosphere, which allows tropical cyclones to develop from small weather disturbances that act as the “seeds.” The researchers think those changes are caused by warming-driven shifts in global atmospheric circulation patterns. “It’s a pretty holistic view,” Wood says of the analysis.

But even if there are fewer tropical cyclones overall, a larger proportion of those that do form are expected to reach higher intensities because global warming is also raising sea-surface temperatures and making the atmosphere warmer and moister—the conditions these storms thrive on. “Once a tropical cyclone forms,” Chand says, “there is a lot of fuel in the atmosphere.”