We may never know when a human jumped on a horse and rode off into the sunset for the first time, but archaeologists are hard at work trying to understand how horses left the wild and joined humans on the trail to global domination. New research purports to have found the earliest evidence of horseback riding.

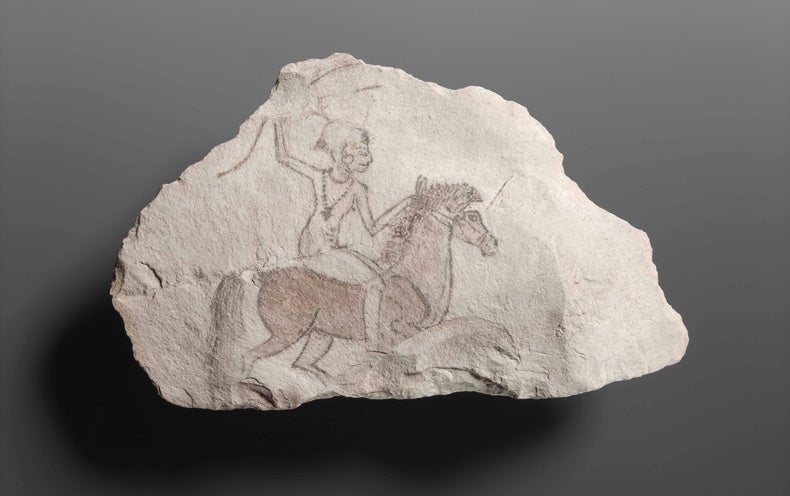

A team of scientists reports that humans may have ridden horses as early as 3000 B.C.E.—some 1,000 years before the earliest known artistic representation of a human astride a horse. The discovery, which is described in a study published on March 3 in Science Advances, hinges on skeletal analysis of human remains found across eastern Europe.

“I always assumed that we would find it at some point,” says Katherine Kanne, an archaeologist at University College Dublin, who was not involved with the new research, about signs that humans were riding horses earlier than previous evidence had suggested. “A lot of us suspected this for a long time, and for it to come true is really exciting to see—and gratifying for sure.”

To date, researchers have assembled only a patchy timeline of how humans have used horses. By about 3500 B.C.E., humans appear to have been milking early domestic horses, a delicate process, which is evidence that the animals were already quite tame. But a recent genetic analysis suggests that the lineage of modern domestic horses didn’t arise until about 2000 B.C.E. That is around the same time that chariot wheels and artistic depictions of horseback riding begin to appear. Both indicate uses that would require fully domesticated animals.

The new study tackles the challenge by focusing on human skeletons. Many of the remains it examines belong to the Yamnaya people, who have been long associated with horses by archaeologists and who swept across much of Eurasia from their origins in modern-day western Russia between 3000 and 2500 B.C.E. “The Yamnaya are extraordinary,” says the study’s co- author Volker Heyd, an archaeologist at the University of Helsinki. He notes that the group’s influence across Europe continues to this day in, for example, the Indo-European languages spoken across the continent.

Heyd and a large group of his colleagues had set out to survey Yamnaya kurgans, or burial mounds, in eastern Europe. These structures and the items they contain are the only remaining traces of the culture. Co-author Martin Trautmann, an anthropologist also at the University of Helsinki, was stunned by a familiar pattern of marks associated with frequent horseback riding on the skeleton of a man in his 30s. These patterns—called “horseman syndrome”—happen as bones adapt to the biomechanical stress caused by repeated movements. “Bones are living tissue in living creatures,” Trautmann says. “You can read life histories from bones.”

Horseman syndrome involves changes to the thigh bones, pelvis and lower spine. Trautmann had seen these alterations in countless skeletons from much later time periods. “Horseback riding is a very specific pattern of biomechanical stress,” he says. “You use muscle groups in a way you usually don’t do in everyday locomotion.”

Trautmann initially hesitated to link the markings to horseback riding but soon found similar patterns on additional skeletons from that same time. All told, the new paper reports five Yamnaya skeletons displaying at least four of six such traits out of a total of 217 skeletons included in the kurgan survey.

Not all the skeletons were preserved well enough to allow the researchers to evaluate every component of horseman syndrome, however, leading to some gaps in their assessments. “It’s a fascinating paper. I absolutely love it,” says Birgit Bühler, an archaeologist at the University of Vienna, who was not involved in the new research. “But I would be cautious because of these missing criteria.”

And because the research focuses exclusively on human remains, not everyone is convinced the analysis shows that humans were riding horses specifically, despite long-standing academic association of the Yamnaya with horses. “Those pathologies might totally be involved with animal transport, but I see no real evidence here to actually link them to horses,” says William Taylor, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, who was not involved with the new research. Unlike horseback riding, scientists don’t have a sense of the traces that riding other types of animals might leave on a human’s skeleton, a gap he says he hopes researchers begin to address.

Trautmann says he suspects that riding animals that are similar enough to horses, such as mules, would leave signs of horseman syndrome. Although he’s satisfied by the scattered horse bones found at Yamnaya sites, he hopes someday scientists analyze those remains for corresponding skeletal signs that a horse regularly carried a rider.