The COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, but in May officials ended its designation as a public health emergency. So it’s now fair to ask if all our efforts to slow the spread of the disease—from masking, to hand washing, to working from home—were worth it. One group of scientists has seriously muddied the waters with a report that gave the false impression that masking didn’t help.

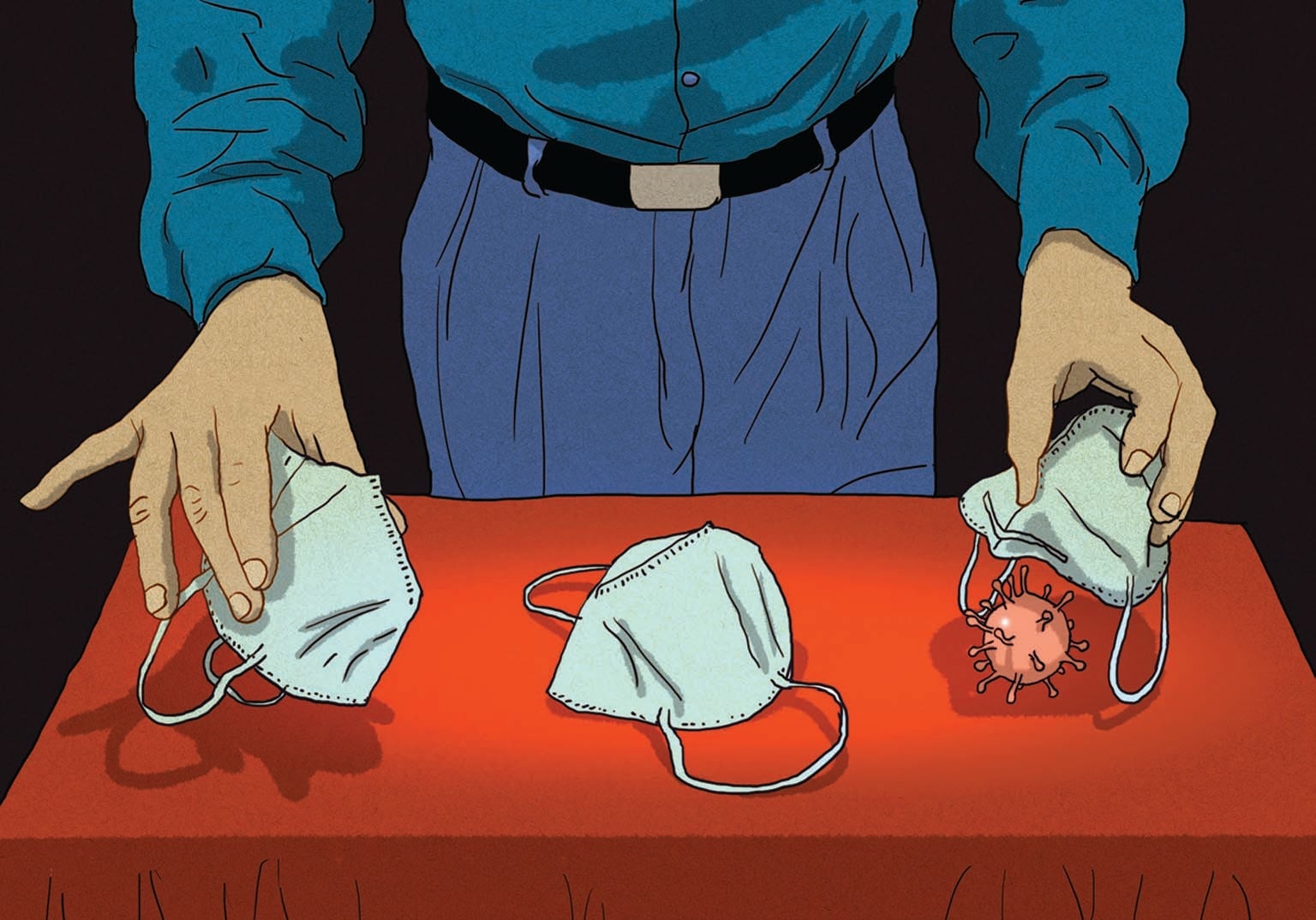

The group’s report was published by Cochrane, an organization that collects databases and periodically issues “systematic” reviews of scientific evidence relevant to health care. This year it published a paper addressing the efficacy of physical interventions to slow the spread of respiratory illness such as COVID. The authors determined that wearing surgical masks “probably makes little or no difference” and that the value of N95 masks is “very uncertain.”

The media reduced these statements to the claim that masks did not work. Under a headline proclaiming “The Mask Mandates Did Nothing,” New York Times columnist Bret Stephens wrote that “the mainstream experts and pundits … were wrong” and demanded that they apologize for the unnecessary bother they had caused. Other headlines and comments declared that “Masks Still Don’t Work,” that the evidence for masks was “Approximately Zero,” that “Face Masks Made ‘Little to No Difference,’” and even that “12 Research Studies Prove Masks Didn’t Work.”

Karla Soares-Weiser, the Cochrane Library’s editor in chief, objected to such characterizations of the review. The report had not concluded that “masks don’t work,” she insisted. Rather the review of studies of masking concluded that the “results were inconclusive.”

In fairness to the Cochrane Library, the report did make clear that its conclusions were about the quality and capaciousness of available evidence, which the authors felt were insufficient to prove that masking was effective. It was “uncertain whether wearing [surgical] masks or N95/P2 respirators helps to slow the spread of respiratory viruses.” Still, the authors were also uncertain about that uncertainty, stating that their confidence in their conclusion was “low to moderate.” You can see why the average person could be confused.

This was not just a failure to communicate. Problems with Cochrane’s approach to these reviews run much deeper.

A closer look at how the mask report confused matters is revealing. The study’s lead author, Tom Jefferson of the University of Oxford, promoted the misleading interpretation. When asked about different kinds of masks, including N95s, he declared, “Makes no difference—none of it.” In another interview, he called mask mandates scientifically baseless.

Recently Jefferson has claimed that COVID policies were “evidence-free,” which highlights a second problem: the classic error of conflating absence of evidence with evidence of absence. The Cochrane finding was not that masking didn’t work but that scientists lacked sufficient evidence of sufficient quality to conclude that they worked. Jefferson erased that distinction, in effect arguing that because the authors couldn’t prove that masks did work, one could say that they didn’t work. That’s just wrong.

Cochrane has made this mistake before. In 2016 a flurry of media reports declared that flossing your teeth was a waste of time. “Feeling Guilty about Not Flossing?” the New York Times asked. No need to worry, Newsweek reassured us, because the “flossing myth” had “been shattered.” But the American Academy of Periodontology, dental professors, deans of dental schools and clinical dentists (including mine) all affirmed that clinical practice reveals clear differences in tooth and gum health between those who floss and those who don’t. What was going on?

The answer demonstrates a third issue with the Cochrane approach: how it defines evidence. The organization states that its reviews “identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria.” The problem is what those eligibility criteria are.

Cochrane Reviews base their findings on randomized controlled trials (RCTs), often called the “gold standard” of scientific evidence. But many questions can’t be answered well with RCTs, and some can’t be answered at all. Nutrition is a case in point. It’s almost impossible to study nutrition with RCTs because you can’t control what people eat, and when you ask them what they have eaten, many people lie. Flossing is similar. One survey concluded that one in four Americans who claimed to floss regularly was fibbing.

In fact, there is strong evidence that masks do work to prevent the spread of respiratory illness. It just doesn’t come from RCTs. It comes from Kansas. In July 2020 the governor of Kansas issued an executive order requiring masks in public places. Just a few weeks earlier, however, the legislature had passed a bill authorizing counties to opt out of any statewide provision. In the months that followed, COVID rates decreased in all 24 counties with mask mandates and continued to increase in 81 other counties that opted out of them.

Another study found that states with mask mandates saw a significant decline in the rate of COVID spread within just days of mandate orders being signed. The authors concluded that in the study period—March 31 to May 22, 2020—more than 200,000 cases were avoided, saving money, suffering and lives.

Cochrane ignored this epidemiological evidence because it didn’t meet its rigid standard. I have called this approach “methodological fetishism,” when scientists fixate on a preferred methodology and dismiss studies that don’t follow it. Sadly, it’s not unique to Cochrane. By dogmatically insisting on a particular definition of rigor, scientists in the past have landed on wrong answers more than once.

We often think of proof as a yes-or-no proposition, but in science, proof is a matter of discernment. Many studies are not as rigorous as we would like, because the messiness of the real world prevents it. But that does not mean they tell us nothing. It does not mean, as Jefferson insisted, that masks make “no difference.”

The mask report—like the dental floss report before it—used “standard Cochrane methodological procedures.” It’s time those standard procedures were changed.