Tilapia skin is rich in collagen, and this structural protein’s abundance has made the fish a popular resource in veterinary and human medicine. Researchers have explored its use in applications from bandaging burn victims and correcting abdominal hernias to mending heart valves and reconstructing vaginas.

Inspired by colleagues in a dozen other specialties, Mirza Melo, a veterinary ophthalmologist in northeastern Brazil’s Ceará state, tested tilapia skin to treat a pervasive problem in her field: corneal ulcers and perforations, particularly in dogs with short snouts. “These are species with very prominent eyes,” she says. “So they get injured often.“

Such corneal injuries are commonly treated by surgically placing a membrane made of horse placenta (also a collagen source but with a lower concentration than tilapia skin, Melo says) over the affected area to help it regenerate. Melo first swapped that membrane for tilapia skin in 2019, when she successfully operated on a Shih Tzu with a severe corneal perforation.

Brazil’s Burn Support Institute and the Federal University of Ceará—home of the Tilapia Skin Project, which pioneered the skin’s use to treat burns—approached her about the surgical technique. With their support Melo began testing a membrane she called the acellular dermal matrix (ADM), made of pure collagen extracted from the fish skin.

Collagen is known to stimulate cellular growth and to “guide the generation of various tissues,” Melo says. A tilapia’s collagen supply and quality remain high throughout the fish’s entire life, whereas horse-placenta collagen varies depending on factors such as the animal’s age and weight, she says.

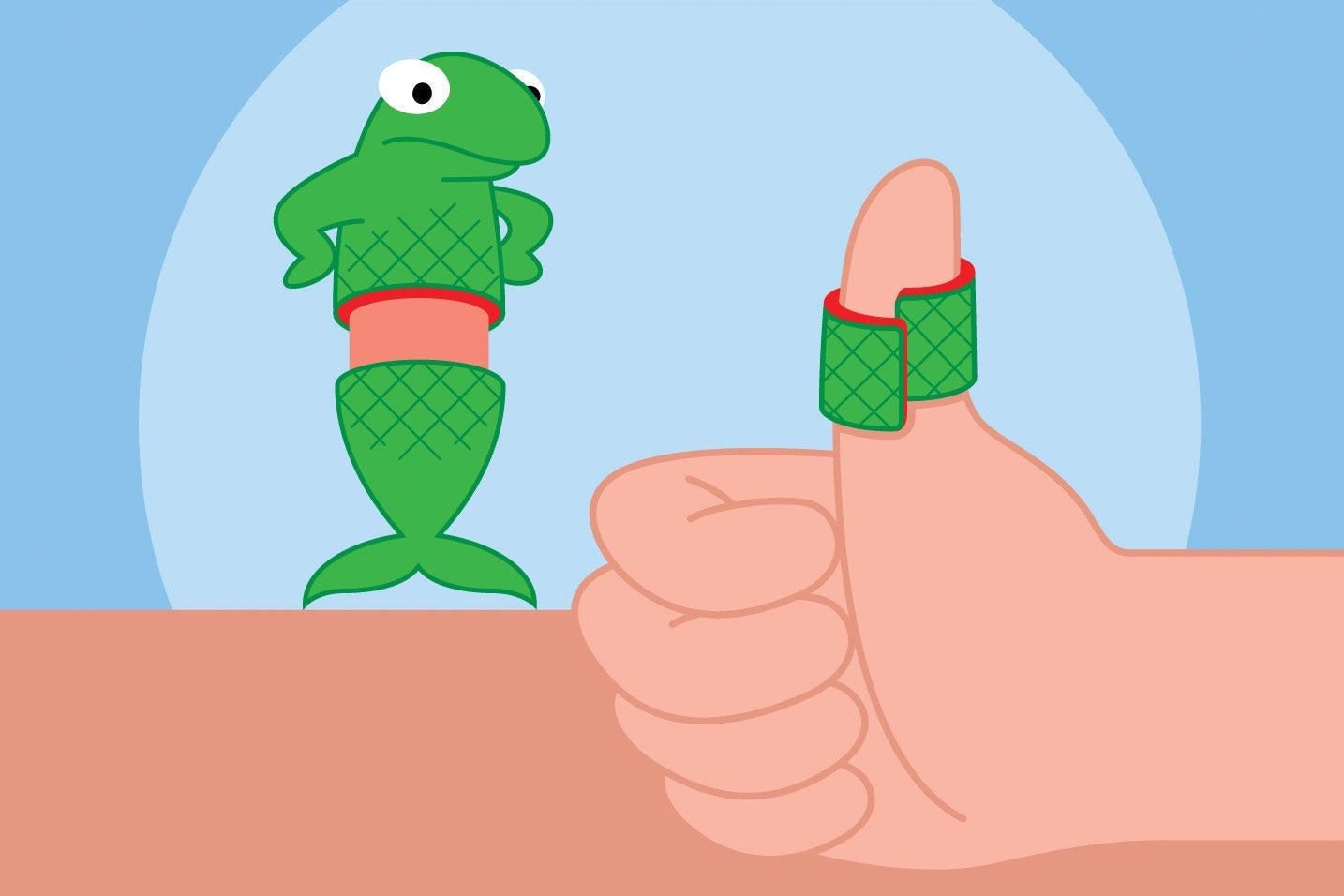

The processed ADM resembles a thick sheet of paper. Veterinarians rehydrate it with saline solution before surgery, then lay it over a dog’s corneal lesion and suture it into place, where it acts as scaffolding for regenerating cells.

The 400-plus dogs Melo has treated so far have shown no pain or problems with infection after surgery. They also healed quickly, with minimal scarring that would affect postsurgical care.

Current corneal repair strategies such as using horse placenta, grafting and transplant have good results—but scarring continues to be a concern, says Robson Santos, a veterinary ophthalmologist not involved in the ADM project. “Tilapia skin is an excellent alternative to the well-established techniques we already have,” he says.

Melo is now looking to use the technique on cats, and she says discussions have already begun on how to adapt it for humans. She also hopes to take her research to the eye’s retina, which is particularly challenging to treat because of its extremely sensitive specialized neurons.

“It’s where we have the most limited resources, in both veterinary and human ophthalmology,” Melo says. “So we hope to get there one day.”