The Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization shattered the U.S.’s already patchwork abortion coverage. States where it was once incredibly challenging to receive this sometimes lifesaving medical procedure banned it outright. In some states, old laws regained their constitutionality, while in others, lawsuits challenging abortion restrictions were struck down. Interestingly, many states that ban or severely restrict abortion are also failing to comprehensively educate their young people about safe sex.

“Sex education is designed to give people the skills, values and attitudes that empower them to have a healthy life,” says Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “Those places that don’t [offer] that are basically just throwing the dice and hoping that the kids will get it.”

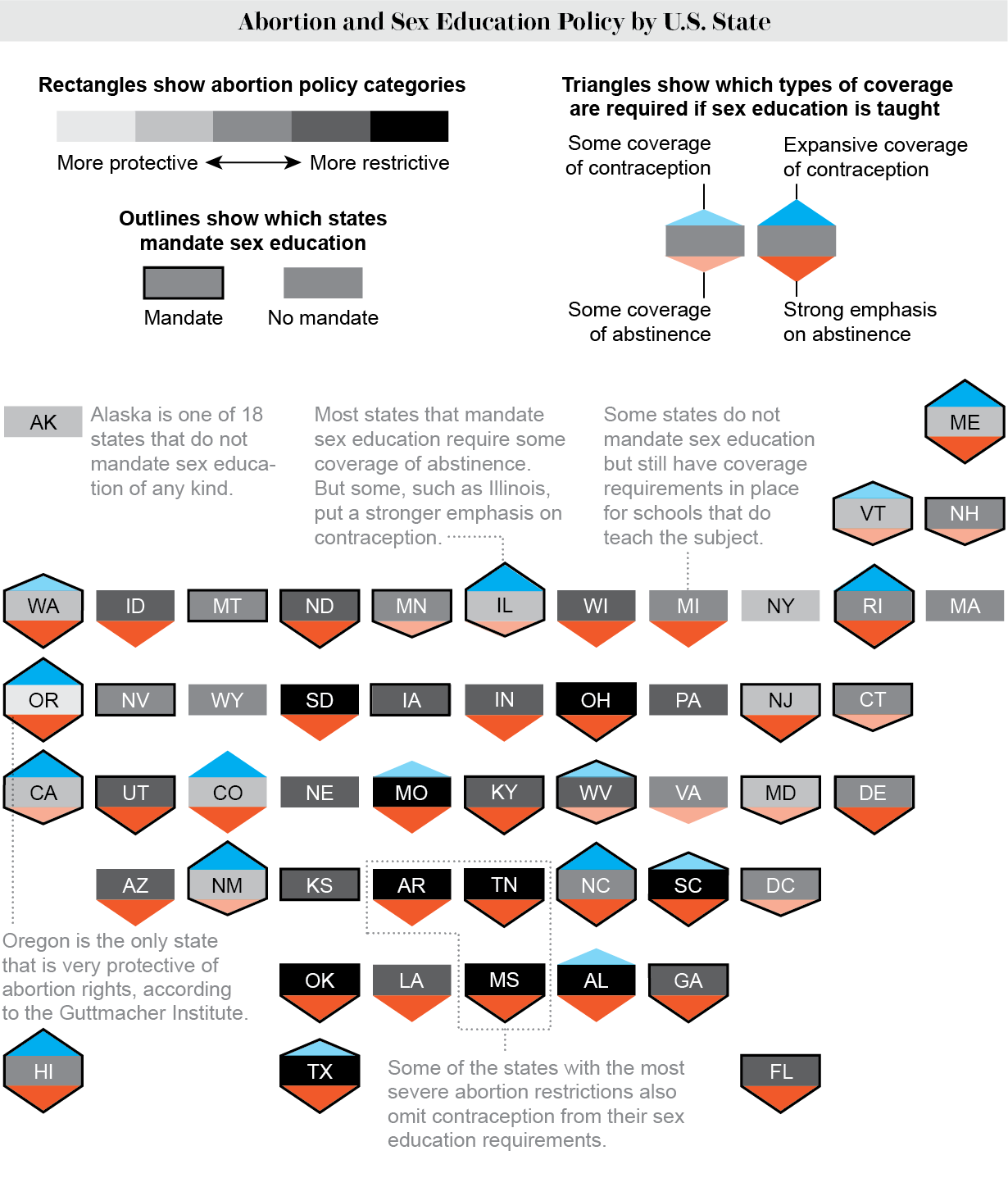

The nonprofit Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) collected data on sex education policies across the country and found that, like abortion coverage, such policies are fragmented. In fact, only 32 states and Washington, D.C., mandate sex education in schools. Of them, 15 states and Washington, D.C., mandate that abstinence-only education be included or emphasized without any coverage of contraceptives, and four states do not specify that the lessons should cover either category.

Among states that do not mandate sex education, 12 have policies in place directing that students be taught about abstinence or contraception if a school decides to provide sex education. Six states neither require sex education nor mandate teachers include these categories when it is taught.

This state-by-state variation hurts youth. “It’s wildly to the detriment of young people,” says Christine Harley, president and CEO of SIECUS. “We are failing young people across this country left and right.” She says that people might not understand the breadth of comprehensive sex education, which is about more than anatomy and how people become pregnant. “It’s about healthy relationships, teaching about how to navigate communication and negotiation, personal safety, consent and decision-making,” Harley explains.

The sex education SIECUS advocates for is trauma-informed and inclusive of all sexual and gender identities, Harley says. Such comprehensive education provides many positive health outcomes for young people. “You see young people delaying [sex], having fewer sexual partners, having fewer unplanned pregnancies, having less transmission of [sexually transmitted infections] and HIV,” Harley says. “These are all things that we want for young people.” Additionally, she says, there is evidence to suggest that comprehensive, evidence-based sex education helps prevent relationship violence and sexual abuse because it teaches young people what red flags to watch out for.

“Young people are smart,” says Elizabeth Nash, principal policy associate for state issues at the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit research and policy organization that works to advance global sexual and reproductive rights. “With information and health care access, young people can make decisions for themselves.” In an ongoing analysis, Guttmacher collects and evaluates state policies and classifies U.S. states on a scale from “most protective” to “most restrictive” of abortion. Now that states can and have banned abortions outright, Nash says, sex education is more important than ever. Comparing the overlap between the places where such education is the least comprehensive to those where abortion is most restricted reveals “it’s basically a circle.”

But banning abortion has not been the only response from states. Nash explains that in states where abortion restrictions are more of a gray area, more conservative legislatures push trigger laws through courts while more liberal-leaning legislatures are shifting toward being more protective. “We have a constitutional amendment to protect abortion rights pending in California, Michigan and Vermont this November,” she says. And there are other states deciding on money allocations for abortion funds. But this isn’t enough in her opinion. “We need the federal government to step in across the board on reproductive health,” Nash says—from protecting abortion to improving contraceptive access to mandating comprehensive sex education. Without comprehensive abortion protections and sex education policies at the federal level, reproductive health with continue to be wildly different across the country.

Most Protective State for Abortion and Sex Ed

Guttmacher considers Oregon the “most protective” state for abortion. “Oregon doesn’t have a gestational age law,” Nash says, so a person can have an abortion at any stage of pregnancy. The state also dedicates resources to providing abortion access: in March $15 million of Oregon’s money was allocated to the Reproductive Health Equity Fund, which will help patients pay for both abortion services and travel costs. “Not very many states have adopted a state fund to pay for abortions”—at least not yet, Nash says.

Oregon is one of the 32 states that mandate sex education. Further, the sex education provided to young Oregonians must be age-appropriate, evidence-based, culturally appropriate and medically accurate. It is also one of the few states whose programs must be inclusive of LGBTQ+ people and include comprehensive discussions about how to maintain healthy relationships. Although the state mandates that abstinence must be emphasized in its sex education programs, there must also be expansive coverage of other contraceptive methods. “We would consider [Oregon] to be an ‘abstinence plus’ state,” Harley says. “Despite the emphasis and the encouragement around abstinence, they’re still doing the best to provide young people with as much information as possible about safer sex practices.”

Least Protective States

In some ways, Nebraska’s sex education policies are diametrically opposed to those in Oregon. “Sex education is not mandated,” Harley says. “Whatever is taught in the classroom, there’s no requirement that it be evidence-based, culturally appropriate or medically accurate.” This might lead to sex education programs that are based on religious, abstinence-only teachings. Young people in Nebraska may be taught that anything sexual outside of a “God-ordained, monogamous, heteronormative marital relationship” is a sinful activity, Harley says.

Nebraska is also a restrictive state when it comes to abortion. The medical procedure is legal until 22 weeks after the first missed period. If a person has not purchased an additional rider insurance policy that adds abortion benefits, however, neither privately nor publicly funded insurance can be used to cover it except in very limited, life-threatening circumstances. Parental consent is required for any minor seeking an abortion, and anyone who wants the procedure must wait 24 hours after their state-mandated counseling to receive treatment.

Nebraska’s state legislature is in the process of restricting abortion even further and attempting a full ban. A filibuster narrowly prevented a trigger ban from passing there earlier this year. For now, Nebraskans can continue seeking the reproductive care that they need.

Abortion is also banned in Mississippi, the state that brought Dobbs in front of the Supreme Court. After the decision overturned nearly 50 years of medical precedent and a Mississippi judge refused to block the state’s 2007 law banning abortion, it went into effect on July 7. The ban makes abortions in Mississippi illegal except in the case of rape—but only if it was reported to police officers—or when the pregnant person’s life is at risk. After a lower court ruled against them, attorneys for Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the state’s only abortion clinic before the ban, filed a request to the Mississippi Supreme Court to block the state law on the same day it went into effect. When the higher court declined to expedite the appeal, the owner of the clinic sold the building. There are no longer any abortion clinics in Mississippi.

“If a state is looking toward banning abortion or has already banned abortion,” Nash says, “then it’s incredibly likely that their sex education policy is either abstinence-only or, at the very least, abstinence-focused.” This is true for Mississippi. The state mandates that sex education be taught to students and that it include abstinence-only curricula. There is no requirement to cover alternative contraceptive methods. Furthermore, teachers, school counselors and nurses are not allowed to tell students that “abortion can be used to prevent the birth of a baby.”

Benjamin asserts that it’s only a matter of time before Roe’s protections are reinstated. He cites past policies that were widely unpopular, such as prohibition, as examples. “I know that our nation makes bad policy decisions on occasion.” he says, “And when we do—and we have very, very terrible things that happen—the public rises up and demands that it be fixed.” He sees a two-tiered approach in the wake of the Dobbs decision. First, abortion access needs to be protected. Second, social support needs to be in place, “which includes comprehensive sex education, making sure that [parents] have paid sick leave and making sure that we provide health insurance coverage,” Benjamin says.

“Even when we reestablished Roe, and we will, as a law of the land,” he adds, “that social agenda will still be intact and important.”