More new human cases of monkeypox have been identified worldwide, with dozens reported in the U.K. alone. The increase comes after previous evidence had suggested there was unknown transmission of the monkeypox virus within the country’s population, according to the U.K. Health Security Agency (UKHSA). Monkeypox is thought to originate in rodents in Central and West Africa, and it has repeatedly jumped to humans. Cases outside Africa are rare and have so far been traced to infected travelers or imported animals.

On May 7 reports surfaced that a person who had traveled to the U.K. from Nigeria had contracted monkeypox. A week later authorities reported two additional cases in London that were apparently unrelated to the first one. At least four of the people recently identified as having the disease also had no known contact with the three previous cases—this suggests unknown chains of infection in the population.

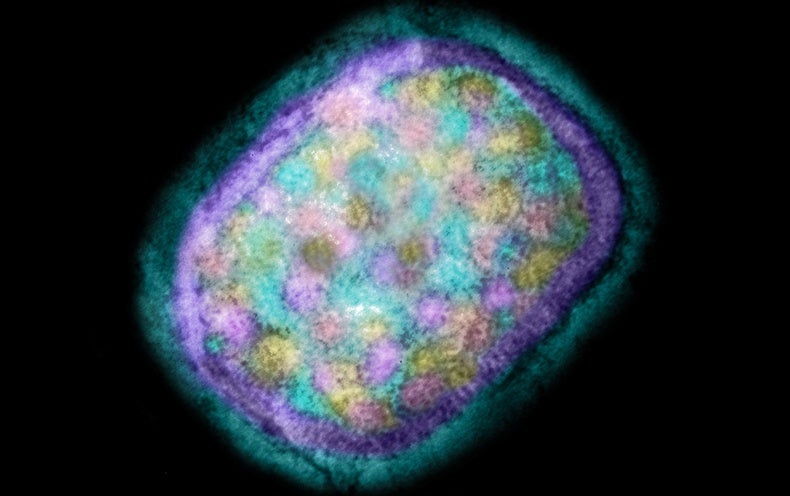

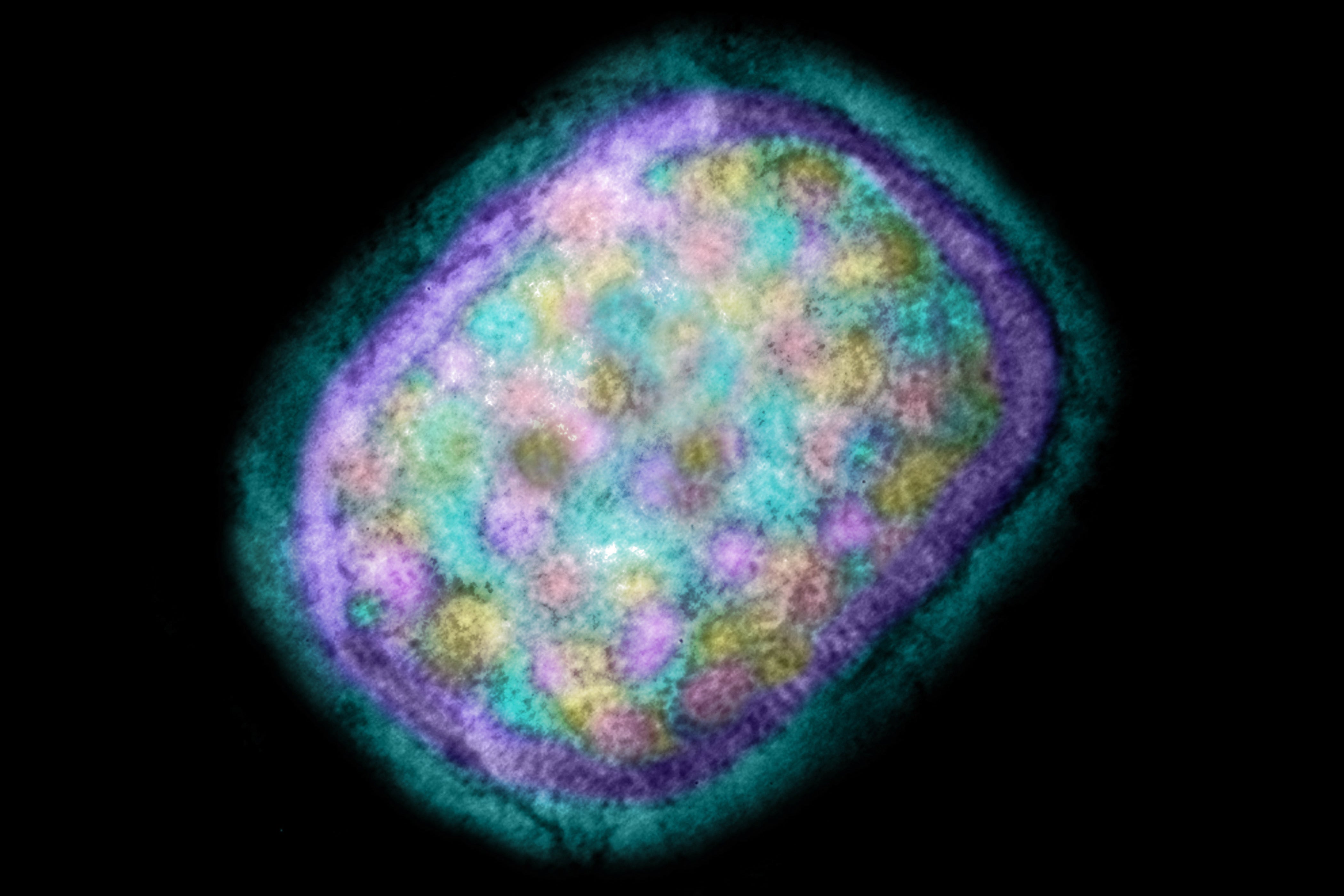

According to the World Health Organization, all of the infected people in the U.K. contracted the West African clade of the virus, a version that tends to be mild and usually resolves without treatment. The infection begins with fever, headache, aching limbs and fatigue. Typically, after one to three days, a rash develops, along with blisters and pustules that resemble those caused by smallpox, which eventually crust over.

“This is an evolving story,” says Anne Rimoin, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles’s Fielding School of Public Health. Rimoin, who has spent many years studying monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, has many questions: At what point in the disease process are the people who were infected? Are these really new cases or older ones that have just now been discovered? How many of them are primary cases—infections traced to contact with animals? How many of them are secondary, or human-to-human, cases? What are the infected people’s travel histories? Are there connections between these cases? “I think that it’s too early to make any kind of definitive statements,” Rimoin says.

All Reported Infections Involve a Mild Version

Many of the infected people in the U.K. are men who have sex with men and contracted the disease in London, UKHSA reports. Some experts think transmission may be occurring in this community but could also be spread by close contact with others, including household members or health care workers, for example. The virus spreads through droplets from the nose or mouth. It can also be transmitted via body fluids, such as from pustules, as well as objects that have come into contact with them. Most experts say close contact is necessary for infection, however.

The cluster of cases in the U.K. is rare and unusual, says Susan Hopkins, UKHSA’s chief medical adviser. The agency is currently tracking the contacts of those infected. Although data from the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the early 1980s and mid 2010s suggest the effective reproduction numbers at those times were 0.3 and 0.6, respectively—meaning each infected person passed the virus to fewer than one person in those populations, on average—there is growing evidence it can spread persistently from person to person under certain conditions. For reasons that are still unclear, the number of infections and outbreaks is increasing significantly—which is why monkeypox is considered a potential global threat.

With the situation still evolving, experts have not immediately raised concerns about widespread international outbreaks. “I’m not all that worried” about the possibility of a larger epidemic in Europe or North America, says Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine. Historically, the virus has mostly been transmitted from animals to people, and person-to-person transmission usually requires close or intimate contact. “It’s not anything nearly as transmissible as COVID, for instance, and not even as transmissible as smallpox,” Hotez says.

The bigger issue, he says, is that the virus crossed over from animals—possibly rodents—in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria and western Africa. “If you look at some of our most troublesome infectious disease threats—whether [they are] Ebola or Nipah or coronaviruses like [those that cause] SARS and COVID-19 and now monkeypox—these are disproportionately zoonotic diseases, diseases transmitted from animals to humans,” Hotez adds.

The proportion of infected people who die from monkeypox is unclear because data are poor. Known risk groups are immunocompromised people and children, and infection during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage. For the Congo Basin clade of the virus, some sources indicate mortality rates of 10 percent or greater, though more recent surveys show case mortalities lower than 5 percent. In contrast, nearly all individuals infected with the West African version survive. Seven people died during the largest known outbreak, which began in Nigeria in 2017, and at least four of them had a weakened immune system.

There is currently no specific medication for monkeypox itself, but the antiviral drugs cidofovir, brincidofovir and tecovirimat may be used. (The latter two are approved for treating smallpox in the U.S.) Health care workers treat the symptoms and try to prevent additional bacterial infections that can sometimes cause problems during such viral diseases. Very early in monkeypox’s course, the illness can be mitigated by administering a vaccine for both monkeypox and smallpox or an antibody preparation obtained from vaccinated individuals. The U.S. recently ordered millions of vaccine doses, which will be manufactured in 2023 and 2024.

Monkeypox Is Becoming More Common

The number of cases in the U.K., along with evidence of ongoing transmission among people outside Africa, provide the latest indication that the virus is changing its behavior. A study by Rimoin and her colleagues showed the rate of cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo may have increased 20-fold between the 1980s and mid-2000s. And the virus has resurfaced in several West African countries years later: in Nigeria, for example, there have been more than 550 suspected cases since 2017, of which more than 240 were confirmed, including eight deaths.

It remains a mystery why more people in Africa are now contracting the virus. The factors that contributed to recent Ebola epidemics, which infected several thousand people in West Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, may play a role. Experts suggest that factors such as population growth and more settlements near forests, as well as increasing interaction with potentially infected animals, favor the transmission of animal viruses to humans. At the same time, viruses spread faster in general because of higher population density, better infrastructure and more travel, possibly leading to international outbreaks.

The spread of monkeypox in West Africa could also indicate that the virus has appeared in a new animal reservoir. The virus can infect a whole range of animals, including many kinds of rodents, monkeys, pigs and anteaters. Infected animals transmit it relatively easily to other types of animals and humans—which is what happened in the first outbreak outside Africa. In 2003 the virus entered the U.S. with African rodents, and these in turn infected prairie dogs that were sold as pets. Dozens of people in the country became infected with monkeypox in that outbreak.

On the Trail of Smallpox

The factor presumed most important in the current spate of monkeypox cases, however, is that population-wide vaccination coverage against smallpox is declining around the world. Smallpox vaccination reduces the likelihood of contracting monkeypox by about 85 percent. Since the end of the smallpox vaccination campaign, however, the proportion of unvaccinated people has been steadily increasing, making it easier for monkeypox to infect humans. Thus, the share of human-to-human transmissions among all infections has risen from about one third in the 1980s to three quarters in 2007. Another factor pointing to reduced vaccinations is that the average age of those infected with monkeypox has increased with the amount of time since the smallpox vaccination campaign ended.

Experts in Africa have warned that monkeypox could change from a regionally widespread zoonosis to a globally relevant infectious disease. The virus may be filling the ecological and immunological niche once occupied by the smallpox virus, wrote Malachy Ifeanyi Okeke of the American University of Nigeria and his colleagues in a 2020 paper.

“Currently, there is no global system in place to manage the spread of Monkeypox,” said Nigerian virologist Oyewale Tomori in an interview published in the Conversation last year. But it is considered highly unlikely that the current outbreak will become an epidemic in the U.K. The risk to the population is so far low, according to UKHSA. Now the agency is looking for more cases and working with partners internationally to find out if there are similar clusters of monkeypox in other countries.

“Once we’ve identified the cases, then we’re going to have to do really thorough case investigations and contact tracing—and then also do some sequencing to really crack down how this virus has been spreading,” Rimoin says. It is possible the virus had been circulating for some time before public health authorities took notice. “If you shine a flashlight in the dark,” she says, “you’re going to see something.”

Until scientists understand how the virus is transmitting, Rimoin adds, “we have to go on what we know already but also be humble—and remember that these viruses are always capable of changing and evolving.”

A version of this article originally appeared in Spektrum der Wissenschaft and was reproduced with permission.